Cooperative Threads

This project helps you understand the following C program.

void child(void* arg) {

printf("%s is running.\n\r", arg);

}

int main() {

thread_init();

thread_create(child, "Child thread");

printf("Main thread is running.\n\r");

thread_exit();

}You have implemented printf in P0, and you will now implement functions thread_init, thread_create, and thread_exit used in this program. Then you shall see its output:

# Possible output #1

Child thread is running.

Main thread is running.

# Possible output #2

Main thread is running.

Child thread is running.These two possibilities demonstrate the concepts of thread and concurrency. Consider a thread as executing a function. Initially, there is only one thread running function main; After main invokes thread_create, another thread is created running function child. Let's call them the main thread and the child thread. Concurrency means that the program does not enforce any ordering between the two threads. Therefore, if the child thread does the printing first, we will observe the first output above. Otherwise, if the main thread does the printing first, we will observe the second possibility.

TIP

We will explain the meaning of cooperative later. The key here is that everything in P1 will only use the three types of CPU instructions explained in P0 (i.e., integer computation, control transfer, and memory access). Again, we have been seriously striving to help you gain a precise understanding of OS concepts (e.g., threads) by connecting the concepts with the exact CPU instructions.

Get started

You will start from the thread branch of egos-2000 which provides printf and _sbrk for malloc just like P0. You can add your P0 solution code to print.c for debug printing. The functions that you need to implement in P1 are listed in thread.h and thread.c.

Lastly, thread.s contains two important helper functions ctx_start and ctx_switch:

ctx_start:

addi sp,sp,-128

SAVE_ALL_REGISTERS

sw sp,0(a0)

mv sp,a1

call ctx_entry

ctx_switch:

addi sp,sp,-128

SAVE_ALL_REGISTERS

sw sp,0(a0)

mv sp,a1

RESTORE_ALL_REGISTERS

addi sp,sp,128

retThe SAVE_ALL_REGISTERS and RESTORE_ALL_REGISTERS are macros with a straightforward definition in context.s. Next, we explain how to use ctx_start to start the execution of a thread, and use ctx_switch to transfer the control flow to a thread that has already been executing. After the explanations, you should be able to implement the 3 functions used by the multithreaded program above, and run that program.

Context switch

We explain the use of ctx_start and ctx_switch with one of the possible executions of the multithreaded program:

- The main thread calls

thread_initandthread_create. - The child thread starts execution, prints, and calls

thread_exit. - The main thread returns from

thread_create, prints, and callsthread_exit.

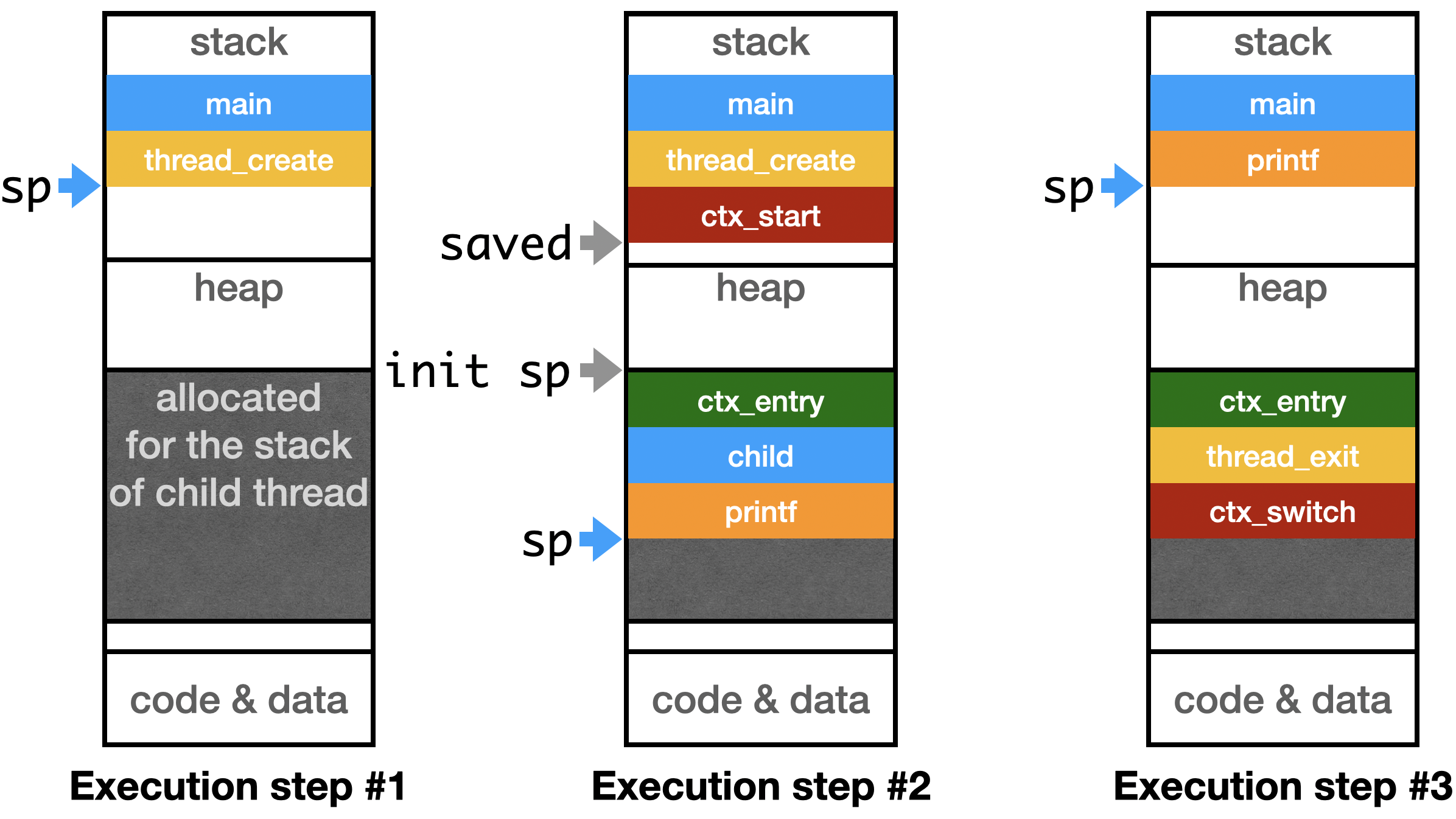

The picture below illustrates the memory layout during the three steps, which contains the four types of memory regions explained in P0 (i.e., code, data, heap, and stack).

What is context?

In step #1, thread_create is preparing to launch the child thread, and an important part of such preparation is to allocate a piece of memory for the child thread's stack, shown as the shaded region. Therefore, we now have two stacks in the memory which is the key feature of multithreaded programs: one stack for each thread.

The sp in the picture indicates the stack pointer. In step #1, the stack pointer points to the main thread's stack, and the program counter points to an instruction of thread_create. Therefore, we say that the CPU is in the context of the main thread. The move from step #1 to step #2 is an example of context switch: the stack pointer now points to the stack of the child thread, and the program counter points to printf. The CPU is thus in the context of the child thread in step #2.

Control flow details

Here are more details about the control flow from step #1 to step #2, and then to step #3.

thread_createinvokesctx_start, and thectx_startregion in the picture has 128 bytes (i.e., the first instruction inctx_startisaddi sp,sp,-128).128=32*4because a 32-bit RISC-V CPU has 32 general-purpose registers, andSAVE_ALL_REGISTERSsaves the value of all these registers on the stack.- The

sw sp,0(a0)inctx_startsaves the 4-byte value of registersp(i.e., thesavedin the picture) at memory addressa0, the first argument ofctx_start. The purpose of savingspat this point is to allow us to switch the CPU context back to the main thread. - The

mv sp,a1inctx_startmoves the stack pointer to a memory address specified bya1, the second argument ofctx_start, shown asinit spin the picture. call ctx_entryinvokes thectx_entryfunction inthread.c. Intuitively,ctx_entryshould find out that the child thread is the one to execute, and thus call functionchild. Afterchildreturns,ctx_entryshould terminate the thread by callingthread_exit.- Lastly,

thread_exitinvokesctx_switchwhich switches the CPU context back to the main thread. The assembly code ofctx_switchis similar toctx_start, so figure out yourself what is happening duringctx_switch. - After

ctx_startandthread_createboth return, the main thread continues to invokeprintfand does the printing as shown in step #3 of the picture.

A few details are still missing: How does thread_create decide the two arguments that it should pass to ctx_start? How does ctx_entry figure out that child is the function to call? These questions lead to the concept of Thread Control Block (or TCB).

Thread control block

The thread control block is a data structure storing the metadata of every thread, including

- thread id: a unique identifier of a thread

- status: the thread’s current execution status

- stack pointer: the saved value of register

spbefore switching to another thread - entry function: the “main” function of a thread (e.g., the

childfunction) - entry function arguments: the arguments for the thread’s entry function

- other metadata that you find helpful

You can implement the thread control block as follows.

struct thread {

int id;

void* sp;

... // Design the rest of struct thread yourself.

};

int current_idx; // TCB[current_idx] is the currently running thread.

struct thread TCB[32]; // Represent TCB as a simple array. You can also use

// a queue data structure as we will explain later.The code below shows how to use the TCB for ctx_start in thread_create.

char* child_stack = malloc(STACK_SIZE);

ctx_start(&TCB[current_idx].sp, child_stack + STACK_SIZE);TCB[current_idx].sp, as a pointer in a 32-bit program, occupies 4 bytes in the memory. &TCB[current_idx].sp is the address of these 4 bytes, and the sw sp,0(a0) instruction in ctx_start stores the 4 bytes of register sp into TCB[current_idx].sp. Unlike int* which stores the address of an integer, void* is used when we simply need to store a 32-bit memory address without any type information. In this case, we simply need to store the address shown by the saved label in step #2 of the picture above.

Note that malloc returns the lowest address of the allocated memory, so child_stack + STACK_SIZE gives us the highest address shown as init sp in the picture. As the second argument of ctx_start, this value is stored in register a1, and thus mv sp,a1 moves the stack pointer from the main thread's stack to the child thread's stack.

Figure out yourself how to store and use the entry function in struct thread -- you need the concept of function pointer in C. A function pointer holds 4 bytes as the address of a function's first instruction in the code region (e.g., the first instruction of function child).

TIP

Both the main and child threads call thread_exit(). When the last thread calls thread_exit(), thread_exit() should call the _end() in thread.s, halting the execution of the whole program. Read the comments at the end of thread.c for more details.

Thread yield

Before you start, let us introduce the last function you need to implement for multithreading, thread_yield. In the 3-step execution discussed above, the CPU context switches back to the main thread only after the child thread exits. However, if the child thread yields before it exits, the child thread will give up the CPU control sooner, and the main thread will resume its execution. Here is an example of two threads yielding to each other.

void child(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

printf("%s is in for loop i=%d\n\r", arg, i);

thread_yield();

}

}

int main() {

thread_init();

thread_create(child, "Child thread");

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

printf("Main thread is in for loop i=%d\n\r", i);

thread_yield();

}

thread_exit();

}In this example, both threads do more printing and, because they yield to each other in the loop, we could see interleaving printings from the two threads. Intuitively, the key of an OS is to insert yields into different tasks so that different tasks run concurrently. Threads yield explicitly by calling thread_yield in P1 and, in P2, we will learn about how the CPU forces a thread to yield without the thread calling thread_yield explicitly. This difference is why P1 is called cooperative threading while P2 is doing preemptive threading.

You can now start to implement the TCB and the following functions in thread.c. Note that struct thread is defined in thread.h which also contains detailed descriptions of these functions. After you finish, you can run the multithreaded programs above, and observe the expected printing.

void ctx_entry();

void thread_init();

void thread_create(void (*entry)(void *arg), void *arg);

void thread_yield();

void thread_exit();TIP

Again, when all the threads have terminated and therefore no thread from the TCB could run, your code should call _end() which halts the whole program. Your code should also free the stack memory of a thread after it terminates. This can be tricky because you should not free the stack memory of the currently running thread when this thread still needs its stack for thread_exit() and ctx_switch(). Moreover, the main thread's stack is not obtained by calling malloc(), so it should not be freed (i.e., after the main thread terminates, do nothing to its stack memory).

Synchronization

Conditional variable

In a multithreaded program, threads often need to wait for a certain condition to become true. For example, in a web browser, a thread that renders a webpage on the screen needs to wait until enough network packets for the webpage have been received. Such waiting is typically handled by a synchronization primitive called conditional variable which is widely used in real-world software practice. Consider a conditional variable as a variable of type struct cv used by multiple threads with 3 operations:

struct cv {

// Define this data structure yourself.

};

void cv_wait(struct cv* condition);

void cv_signal(struct cv* condition);

void cv_broadcast(struct cv* condition);Let cond denote a condition that some threads need to wait for, and let cond_cv denote a conditional variable defined in the program for cond. A thread could wait for this condition using a loop while(!cond) cv_wait(&cond_cv);. After such a loop, the thread can assume that condition cond is true and thus proceed with its work. If cond is true right before the loop, the thread will skip the loop without calling cv_wait at all.

If cond is false before the loop, the thread will call cv_wait which makes the thread yield. And if no other thread calls cv_signal or cv_broadcast on &cond_cv, the CPU context will never switch back to the waiting thread. The point is that, if another thread finds cond to be true after doing some work, this other thread could call cv_signal or cv_broadcast on &cond_cv in order to wake up the waiting thread.

Technically, struct cv should maintain an array or queue of struct thread just like the TCB. Upon cv_wait, the struct thread of the currently running thread is removed from the TCB and added to the conditional variable. This thread will never be switched back to until its struct thread is added back to the TCB. To this end, cv_signal will remove one struct thread from a conditional variable and add it back to the TCB. And cv_broadcast does the same for all struct thread in a conditional variable.

In this project, we only ask you to implement cv_wait and cv_signal, as well as function cv_init for initializing struct cv, so you can run the following multithreaded program.

Producer-consumer

A classic problem in computer science is the bounded-buffer producer-consumer problem. In the example below, we have a buffer with a fixed size of 3. A program could create many threads, each being a producer or a consumer (i.e., running either produce or consume as the entry function). Producers put items into the buffer while consumers remove items. The constraint is that producers need to wait if the buffer is full, and consumers need to wait if the buffer is empty. Therefore, we have two conditional variables nonempty and nonfull, and the associated conditions are highlighted in the code below.

void* buffer[3];

int count = 0;

int head = 0, tail = 0;

struct cv nonempty, nonfull;

void produce(void* item) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

while (count == 3) cv_wait(&nonfull);

// At this point, the buffer is not full.

buffer[tail] = item;

tail = (tail + 1) % 3;

count += 1;

cv_signal(&nonempty);

}

}

void* consume() {

while (1) {

while (count == 0) cv_wait(&nonempty);

// At this point, the buffer is not empty.

void* result = buffer[head];

head = (head + 1) % 3;

count -= 1;

cv_signal(&nonfull);

}

}Your job is to implement struct cv and the three functions. You may also need to modify the code for TCB and the thread_* functions (e.g., when a thread calls thread_yield() in cv_wait(), remove its struct thread from the TCB). However, you should not modify the function interface defined in thread.h. After you finish, run the producer-consumer code above, and add some debug printing to see what happens.

Use the queue data structure

When representing the TCB and the waiting threads in a conditional variable, you can use a fixed-length array. Alternatively, you can use the queue data structure. The standard library provides sys/queue.h which you can use to define a singly-linked list as a queue.

#include <sys/queue.h>

struct thread {

int id;

...

SLIST_ENTRY(thread) next; // Next pointer for the singly-linked list.

};

SLIST_HEAD(TCB, thread) TCB;

void example_TCB_operations() {

struct thread * t3;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

struct thread * t = malloc(sizeof(struct thread));

t->id = i;

if (i == 3) t3 = t;

SLIST_INSERT_HEAD(&TCB, t, next);

}

// Iterate through all the 5 threads.

struct thread * iter;

SLIST_FOREACH(iter, &TCB, next) printf("thread %d\n\r", iter->id);

// Remove t3, and iterate the 4 threads left.

SLIST_REMOVE(&TCB, t3, thread, next);

free(t3);

SLIST_FOREACH(iter, &TCB, next) printf("thread %d\n\r", iter->id);

}You can ask ChatGPT for more examples of using sys/queue.h, and you can certainly use other data structures in sys/queue.h such as TAILQ -- TAILQ supports INSERT_TAIL in addition to INSERT_HEAD.

Accomplishments

You have finished reading most of grass/kernel.s in egos-2000 which is very similar to ctx_switch. The proc_yield function in grass/kernel.c is similar to thread_yield. You will read and modify proc_yield in P2, and finish reading the rest of grass/kernel.c in P3. Indeed, you will finish reading everything under grass after P3.

TIP

Here is a quote from the Wikipedia page for cooperative multitasking, "Cooperative multitasking was the primary scheduling scheme for 16-bit applications employed by Microsoft Windows before Windows 95 and Windows NT, and by the classic Mac OS."