File System

In the previous project, you have seen how to read and write disk blocks, and you will now study how to build a file system. A file system uses the disk to provide the abstractions of files and directories (aka. folders), which you should have been familiar with through your everyday interactions with operating systems (e.g., Finder in MacOS). There are numerous file systems, and many of them are based on an abstraction called inode. We thus start by explaining this important file system abstraction.

Inode and inode store

Consider an inode as a number of blocks and a file system as an array of inodes. Say a file system maintains 1024 inodes, and each inode holds the information of a file or a directory. For example, inodes in a file system could be used as follows.

- Inode #12 holds 1 disk block for a small text file.

- Inode #103 holds 31 disk blocks for the executable file of the

catcommand. - Inode #781 holds 1 disk block for the

/bindirectory recording the information of all files under directory/bin. This directory contains executable files of commands likecat.

The mkfs tool gives a simple and concrete example of how inodes are used in egos-2000.

Use of inodes in mkfs

When you type make install or make qemu in egos-2000, the command will compile and run tools/mfks.c which produces a disk image file. Below is part of its output.

> make install

...

[INFO] Load ino=0, 34 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=1, 48 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=2, 26 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=3, 15 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=4, 15 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=5, 349 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=7, cat.elf: 15600 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=8, tcp_demo.elf: 10680 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=9, loop.elf: 11188 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=10, cd.elf: 15644 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=11, video_demo.elf: 9388 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=12, crash1.elf: 16772 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=13, crash2.elf: 9432 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=14, ls.elf: 10408 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=15, udp_demo.elf: 9832 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=16, echo.elf: 10144 bytes

[INFO] Load ino=6, ./ 6 ../ 0 cat 7 tcp_demo 8 loop 9 cd 10 video_demo 11 crash1 12 crash2 13 ls 14 udp_demo 15 echo 16

...Let's take a closer look at these 17 inodes numbered from #0 to #16.

Inodes for directories

Inode #0, #1, #2, #3, #4, and #6 are used for directories. The table below summarizes how the code in tools/mfks.c uses these inodes.

| Inode | Corresponding directory | Bytes stored in the inode |

|---|---|---|

| #0 | / | ./ 0 ../ 0 home/ 1 bin/ 6 |

| #1 | /home | ./ 1 ../ 0 yunhao/ 2 rvr/ 3 yacqub/ 4 |

| #2 | /home/yunhao | ./ 2 ../ 1 README 5 |

| #3 | /home/rvr | ./ 3 ../ 1 |

| #4 | /home/yacqub | ./ 4 ../ 1 |

| #6 | /bin | ./ 6 ../ 0 cat 7 tcp_demo 8 loop 9 cd 10 video_demo 11 crash1 12 crash2 13 ls 14 udp_demo 15 echo 16 |

First, every directory contains ./ and ../ corresponding to itself and its parent directory. For example, the parent directory of both /bin and /home is /, illustrated by the ../ 0 part of inode #1 and #6. In general, egos-2000 uses the format {name} {inode no} ... to represent a directory. If a {name} ends with /, this name would represent a sub-directory (e.g., rvr/ in inode #1). Otherwise, this name represents a file (e.g., cat in inode #6). We use this naming convention for directories because it is simple. In most file systems, inodes will record more information such as the size or creation time of a file or directory.

All the inodes in this table hold fewer than 512 bytes, so they all hold only one disk block.

Inodes for files

Inode #5 and #7..#16 are used for files. For example, as shown in the table, inode #5 is for /home/yunhao/README which is a short text file. The content of this text file is defined by the 349 bytes of contents[5] in tools/mkfs.c. Since 349 is smaller than the block size of 512 bytes, inode #5 also holds only one disk block for this README file.

As shown in the mkfs printing above, inode #7..#16 are used for the binary executable files of user commands, and they hold more than one disk block because each of the executable files is larger than 512 bytes. For example, command echo corresponds to inode #16 which holds 10144 bytes (i.e., ceil(10144/512)=20 disk blocks).

Lastly, NINODES is defined as 128 in header file library/file/inode.h, and mkfs uses NINODES to initialize the file system. This means that the file system supports 128 inodes in total, but only 17 of them are used when egos-2000 starts to boot.

TIP

Our goal is to give you a concrete and minimal example of how a file system could be organised as an array of inodes. Make sure that you see how different inodes can hold different numbers of disk blocks, and how an inode can be used as either a file or a directory. In the rest of P6, we will focus on the inode abstraction, and ignore how a file system maps a file or directory to an inode number.

The inode store interface

In addition to NINODES, the header file library/file/inode.h defines inode_intf.

typedef struct inode_store* inode_intf; /* inode store interface */

struct inode_store {

int (*getsize)(inode_intf self, uint ino);

int (*setsize)(inode_intf self, uint ino, uint newsize);

int (*read)(inode_intf self, uint ino, uint offset, block_t* block);

int (*write)(inode_intf self, uint ino, uint offset, block_t* block);

void* state;

};In short, inode_store defines the file system interface in egos-2000, and there are two file systems (i.e., file0.c and file1.c under library/file) implementing this interface. In particular, each file system implements 4 functions read, write, getsize and setsize, and maintains some in-memory state. A pointer needs 4 bytes, so struct inode_store simply holds 20 bytes, and the first 16 bytes hold the addresses of the 4 interface functions (i.e., the address of their first instruction).

If you are familiar with object-oriented programming, you may consider inode_store as an interface (aka. template), and a file system as a class with a local variable and four methods implementing this interface. This explains the self argument of the interface functions, so a file system can access its in-memory state using self->state. In C, self holds 4 bytes as the address of the 20-byte struct inode_store.

For read and write, there are 3 more arguments: ino is the inode number, offset is the block number, and block is the memory address of 512 bytes holding the block data. For example, as we have seen, the executable of echo maps to inode #16 which holds 20 blocks. We can thus read inode #16 with an offset in range 0..19.

// block_t defined in library/file/disk.h

#define BLOCK_SIZE 512

typedef struct block {

char bytes[BLOCK_SIZE];

} block_t;

// This block variable holds 512 bytes in the memory.

block_t block;

// Given `inode_intf fs`, read block #4 from block #0..#19 of inode #16.

fs->read(fs, 16, 4, &block);A simple file system

We now explain a simple file system in library/file/file0.c which implements the inode store interface inode_intf. We start with the mydisk_init function.

inode_intf mydisk_init(inode_intf below, uint below_ino) {

inode_intf self = malloc(sizeof(struct inode_store));

self->getsize = mydisk_getsize;

self->setsize = mydisk_setsize;

self->read = mydisk_read;

self->write = mydisk_write;

self->state = below;

return self;

}The code allocates 20 bytes for the inode store interface, and sets the 4 interface functions as the mydisk_* functions defined in file0.c. Then below is recorded as self->state since the file system needs below for reading and writing the disk. For example, in apps/system/sys_file.c, there is another inode store called disk which simply reads or writes the disk with an offset, ignoring the inode number. A pointer to this disk variable is passed to mydisk_init as the below argument (i.e., mydisk_init(&disk, 0) in sys_file.c).

After assigning &disk to self->state in the mydisk_init function, the file system read and write functions can use self->state to read the disk as follows.

#define DUMMY_DISK_OFFSET(ino, offset) ino * 128 + offset

int mydisk_read(inode_intf self, uint ino, uint offset, block_t* block) {

inode_intf below = self->state;

return below->read(below, 0, DUMMY_DISK_OFFSET(ino, offset), block);

}

int mydisk_write(inode_intf self, uint ino, uint offset, block_t* block) {

inode_intf below = self->state;

return below->write(below, 0, DUMMY_DISK_OFFSET(ino, offset), block);

}This simple file system assumes that every inode holds at most 128 blocks, and operations to (ino, offset) are directly translated to reading or writing disk block ino*128+offset. This is probably the simplest way of implementing the inode store interface and supporting a file system that is barely enough to boot egos-2000.

TIP

The mydisk_getsize and mydisk_setsize functions simply print out an error and halt, meaning that they are not used when booting egos-2000. You will start from here and implement your own file system in the mydisk_* functions in file0.c. Make sure to set FILESYS = 0 in Makefile, so mkfs and egos-2000 run your file system code. Specifically, after make install, you should see MKFS is using *mydisk* instead of MKFS is using *treedisk*.

A sophisticated file system

Your job in this project is to implement some more sophisticated data structure for the inode store interface functions. When you modify such data structures, you typically need to read a disk block into memory, apply your modifications in the memory, and write the block back to the disk. The data structures involved here are not complicated, but students often forget to apply their modifications in the memory back to the disk, leading to subtle bugs.

Regarding the data structure, you will implement a few linked lists similar to how the FAT file system is organised. We now explain how you could maintain one linked list for each inode, and one linked list for all the unused blocks on the disk.

Linked list

Suppose inode #28 has 3 blocks: block #100, #202 and #432 on the disk. We can then use a simple linked list data structure to represent this inode as follows.

struct inode {

int size, head;

} inodes[128];

inodes[28].size = 3;

inodes[28].head = 100;

struct entry {

int next;

} FAT_entry[DISK_SIZE / BLOCK_SIZE];

FAT_entry[100] = 202;

FAT_entry[202] = 432;

FAT_entry[432] = -1;We call it FAT_entry because it is similar to how the FAT file system maintains a linked list. However, if you define inodes and FAT_entry in C like above, they will be in the memory. Instead, we should write these two arrays to the disk so that the file system information still exists on the disk after we power off the computer.

Create the disk layout

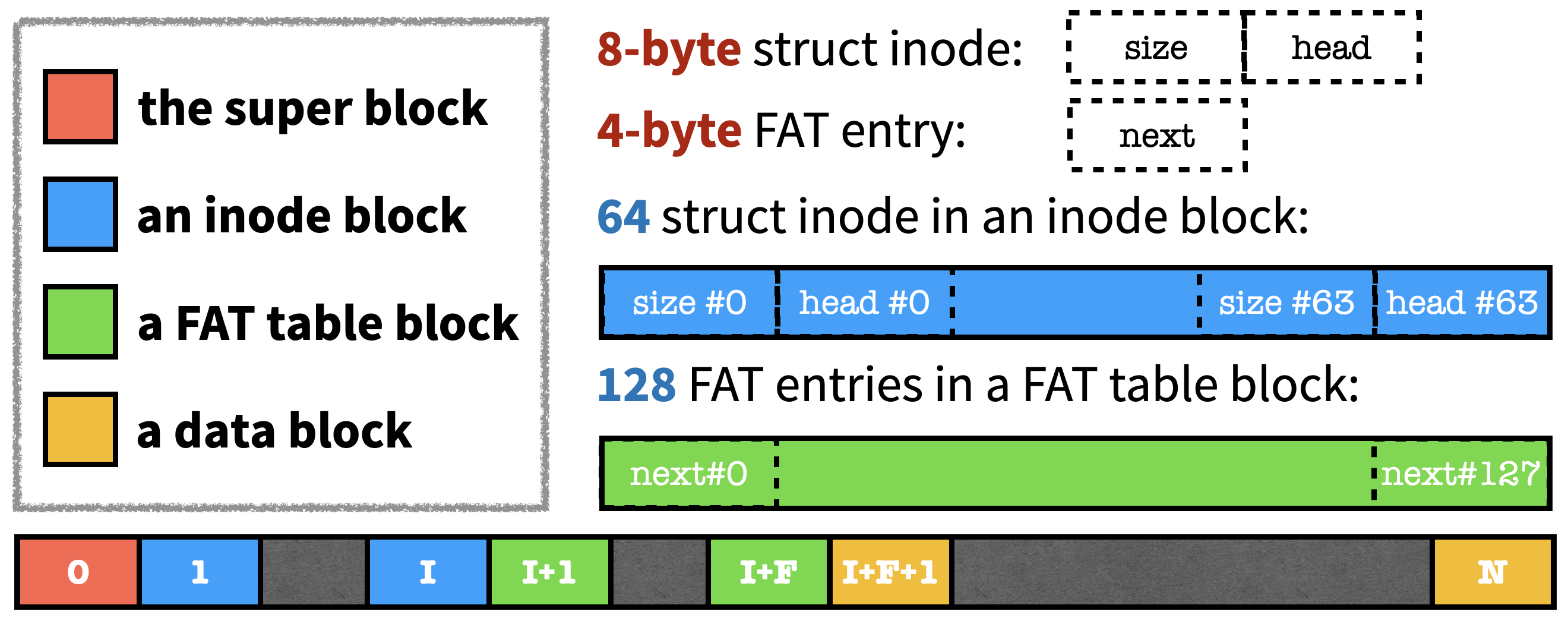

This picture shows how you could put the linked list data structures on the disk.

We split the disk into 4 regions. The first block is called the super block. The next I blocks are called inode blocks, holding the inodes array. The next F blocks are called FAT table blocks, holding the FAT_entry array. All the other blocks starting from I+F+1 are used as data blocks. Since the size of struct inode and struct entry are 8 and 4 bytes, a block can hold 64 struct inode and 128 struct entry.

Therefore, for FAT_entry[100] = 202, we can read block I+1 into memory as an array of 128 entries, modify entry #100, and write it back to the disk. Similarly, for FAT_entry[202], we can read block I+2 into memory, modify entry #74 (i.e., 202%128==74), and then write it back to the disk. Modifying the inodes array with disk blocks 1..I is similar.

Your first task is to implement the mydisk_create function according to the picture above. This function initializes the file system on the disk, a process also known as disk formatting. Specifically, you will do the following.

- Calculate

IandFbased on the number of inodes and the disk size. - Set the

sizeof all the inodes to 0, and set theheadof all the inodes to -1. - Create a linked list containing blocks

I+F+1..N, which is called the initial free list. - Define a data structure for the super block which records

I,F, as well as the head of the initial free list, and write this data structure to the super block. - You don't have to initialize the data blocks.

After the steps above, we will have a file system with all the inodes being empty, and all the data blocks in the free list. You could also read the treedisk_create function in library/file/file1.c as a reference.

TIP

Many file systems maintain a tree data structure instead of linked lists. The most widely-used one is probably B-tree which has a query complexity much lower than linked lists. Indeed, our solution code for this project runs slower than treedisk on QEMU, reflecting the difference in complexity.

Read and write an inode

Your next task is to implement the mydisk_read and mydisk_write functions. At a high level, mydisk_read involves the following steps.

- Read an inode block, and find the

struct inodecorresponding to theinoargument. - Check that the

offsetargument is smaller than thesizefield in thestruct inode. - Traverse from the start of the linked list (i.e., the

headfield) byoffsettimes, and thus find the disk block number for the data block. - Read the data block into the

blockargument ofmydisk_read.

The steps for mydisk_write are similar with one key difference. If the offset argument is larger than (or equal) the size field in the struct inode, remove offset-size+1 blocks from the free list, and add these blocks to the inode. In other words, when writing to a large offset, you should expand the size of the inode by taking blocks from the free list. This is likely the trickiest part in this project, and make sure that you have updated all the 4 regions in the disk layout correctly.

After implementing the two functions, egos-2000 should be able to boot and run normally.

Get and set inode's size

You can now implement mydisk_getsize and mydisk_setsize. getsize should be easy since it is basically the first step of mydisk_read. For setsize, start by implementing the case of nblocks being 0. For a non-zero nblocks, you can try to design helper functions shared by setsize and write which change the size of an inode.

Since egos-2000 does not use these functions, we provide a separate testing framework.

Test your file system code

We provide a testing framework for your file system code in this repo. Specifically, you can replace the file0.c in the repo with your code, and follow the instructions in the README. To write a test case, you write a trace file similar to the trace.txt in this repo.

W:0:0:123456789

W:1:0:1234567

W:1:1:333333

R:0:0:123456789

R:1:0:1234567

R:1:1:333333W:1:0:1234567 means to issue a write operation to your file system with inode #1, offset 0, and block data filled by the number 1234567. R:1:0:1234567 means to read from your file system with inode #1 and offset 0, and then check whether the block data returned by your file system still holds the number 1234567.

You should write a lot more test traces that are more complex than trace.txt, testing your file system code comprehensively. Remember to examine all the corner cases.

Accomplishments

You have gained hands-on experience with the abstraction of inode, file, and directory. In terms of code reading, you have finished library/file and tools/mkfs.c. We touched a bit of apps/system/sys_file.c when explaining mydisk_init, and you can finish reading this short file which serves all file system requests in egos-2000 as a system process.